Library of the History of Autism Research

Insensitivity to children: Responses of undergraduates to children in problem situations (1)

Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 1973, 1,2, pp. 169-180

A study focused on insensitivity of adults to children was presented and discussed. The responses of 100 male and 100 female college undergraduates to hypothetical parent-child problem situations indicated a general lack of communication concerning the child's and their own feelings. However, when the problems involved adult needs being aroused and thwarted, the Ss' responses were both more insensitive and destructive than when the confrontation centered around only the child's aroused needs. In the latter case the Ss did focus their communications more on the child's feelings and how he or she could express them. The results have implications for understanding effective adult behavior and reciprocal adult-child influences on the development of child-behavior dysfunctions.

Our understanding of the development and maintenance of many child-behavior dysfunctions increases with an increase in our understanding of adult-child interaction and communication patterns (Haley, 1963; Leighton, Stollak, and Ferguson, 1971; Wimberger and Kogan, 1968). Detailed analyses of such interaction have also proven useful in attempts to modify directly deviant child behavior at home (Hawkins, Peterson, Schweid, and Bijou, 1966; Patterson, 1971) and in the classroom (Buckley and Walker, 1970; Patterson, 1971; Sulzer and Mayer, 1972).

Yet aside from the behavior-modification literature, there have been few observational or experimental studies in the important area of adult reactions to children in specific problem situations. All children encounter daily situations (especially in relationships with adults) that are disappointing and frustrating, that generate anxiety and arouse anger. It is in these critical moments that we can obtain valuable information concerning those specific adult attitudes and messages that significantly affect the child's feelings toward himself and others. Often, during such moments, the child learns many of the escape and avoidance responses that distinguish varieties of behavior dysfunctions.

However, a limitation of almost all investigations involving observation�either of those examining adult-child interaction in a playroom (e.g., Hatfield, Ferguson, and Alpert, 1967; Saxe and Stollak, 1971) or of those employing naturalistic observation at home (e.g., Baumrind, 1967, 1971)�can be traced to the infrequency of need-arousing activities. For many reasons, the interaction viewed under these conditions often does not simulate the daily problem situations encountered by children. As an attempt to overcome this limitation, the present study, using a procedure similar to that developed by Jackson (1966), confronted adults with a series of hypothetical problem situations and asked them to write their exact reactions to such situations. Such a projective procedure enables the gathering of data from a large number of Ss quickly but does not, of course, necessarily yield data predictive of actual social interaction.

Theory and research in adult-child interaction has also focused on specifying the adult behavior that should maximize the development and maintenance of positive prosocial child behaviors, including children's feelings of esteem, self-reliance, and self-control and interpersonal skills (Axline, 1969; Baumrind, 1967, 1971; Coopersmith, 1967; Dreikurs, 1968; Ginott, 1966; Gordon, 1970; Moustakas, 1966). One goal of the present study was to describe the responses of male and female adults (in this case college undergraduates) along affective and behavioral dimensions indicative of sensitivity to children. The literature suggests that effective adults would respond as follows: (a) clearly indicate awareness of child feelings, (b) help the child understand the relationship between his feelings and behavior and the adult's feelings and behavior, and (c) help the child find appropriate outlets for his or her feelings, needs, and wishes.

Another goal was to explore Gordon's (1970) interesting speculation that sensitivity to children expressed by adults is to some extent dependent on whose needs, the child's or the adult's, are most affected in a problem situation. Gordon (1970) designated "child-owned" problem situations as situations in which the child is being thwarted in satisfying a need. The situation is not a problem for the adult because the child's behavior in no objective or tangible way interferes with the adult satisfying his own needs. In "adult-owned" problem situations, the child is satisfying his own needs but in so doing interferes with the adult need's being satisfied. A situation in which both the child and adult's needs are equally aroused and thwarted is termed a "child-adult equally owned" problem situation. Gordon (1970) also specified 12 categories of ineffective messages that have destructive effects on the adult-child relationship and ultimately on the child's mental health. The present study tested Gordon's contention that when the needs of adults are aroused, the adults would be more ineffective in their communication than when the child "owned" the problem.

METHOD

Subjects

To obtain Ss for a project involving training in communication skills (Stollak, 1973), the following advertisement was placed in the University newspaper:

If you are a college sophomore or junior and interested in helping young children with emotional problems and/or learning about and practicing techniques which could help you become a more effective parent, teacher or child care worker, and are willing to invest 3-4 hours a week during the Fall, Winter and Spring quarters in an intensive practicum experience please come to...

Over 400 male and female students appeared and were told that their scores on several instruments would be used to select participants in the project. The questionnaires analyzed for this research (and described in the following section) consisted of 100 male and 100 female protocols selected at random from the larger pool of over 400. Approximately 30% of the questionnaires included in the sample were completed by psychology majors, 44% by "social service" majors (education, nursing, premedical, social work), and 26% by others, including undergraduates who had no major.

Questionnaire

Among the instruments was a "Sensitivity to Children" (STC) questionnaire. (4) The instructions were as follows:

A series of situations will be found on the following pages. You are to pretend or imagine that you are the parent (mother or father) of the child described. All the children in the following situations are to be considered six years old. Your task is to write down exactly how you would respond to the child in each of the situations, in a word, sentence or short paragraph. Write down your exact words and/or actions, but please do not explain why you said or did what you described. Again, write down your exact words and/or actions as if you were writing a script for a play or movie (e.g., do not write "I would reassure or comfort him"; instead, for example, write "I would smile at him and in a quiet voice say, "Don't worry, Billy, daddy and I love you").

The first four of 16 items were as follows:

(1) You are having a friendly talk with a friend on the phone. Your son Carl rushes in and begins to interrupt your conversation with a story about a friend in school.

(2) You and your husband (wife) are going out for the evening. As you are leaving you both say "goodnight" to your son Frank. He begins to cry and pleads with you both not to go out and leave him alone even though he doesn't appear sick and the babysitter is one he has previously gotten along well with.

(3) After hearing a great deal of giggling coming from your daughter Lisa's bedroom, you go there and find her and her friends Mary and Tom under a blanket in her room with their clothes off. It appears that they were touching each other's sexual parts before you arrived.

(4) Your daughter Barbara has just come home from school; silent, sad-faced, and dragging her feet. You can tell by her manner that something unpleasant has happened to her.

The remaining items involved (5) Stealing; (6) Sibling fighting; (7) Bedtime disagreement; (8) Hiding an accident; (9) Masturbation; (10) Cigarette smoking in a group; (11) Temper tantrum in public; (12) Child denouncing self; (13) Child questioning parental love; (14) Child requesting support after punishment by spouse; (15) Child expressing anger at school; and (16) Child expressing fear of being attacked by older children. These problems were derived from reports of parents in various parent-education courses taught by Stollak over the last 5 years. The items have been rewritten several times to minimize ambiguities and eliminate certain interpretations.

Along with the responses being coded into various categories, the 16 STC items were divided into adult-owned, child-owned, and child-adult equally owned problems. Three coders independently rated each STC item into one of the three possibilities, and the few disagreements were resolved by discussion. For example, item 1 was considered adult-owned, item 2 child-adult equally owned, item 3 adult-owned, and item 4 child-owned.

Scoring the STC

Responses on the STC were scored for the following categories:

(1) Is there a statement of the child feelings? "You seem sad." "You look happy."

(2) Is there a statement of the adult feelings? "I feel sad." "I am happy,"

(3) Is there a relating of child feelings to adult feelings? "When you look upset, I become sad."

(4) Is there a relating of child feelings to adult behavior? "When you look upset, I try to cheer you up."

(5) Is there a relating of child behavior to adult feelings? "When you yell, I get angry."

(6) Is there a relating of child behavior to adult behavior? "When you yell, I tell you to stop."Are general directions given to the child to change behavior? "You must stop playing now."

(7) Is the child given specific directions regarding how he is to act-specific ways to act in the present? "You must stop hitting your sister and apologize."

(8) Is the child given specific directions regarding how he is to act in the future? "You must never hit your sister; come to me instead."

(9) Is the child given specific directions regardin4 present feelings-the way to handle feelings now? "If you are angry at your sister, tell her so, right now."

(10) Is the child given specific directions regarding future feelings-the way to handle feelings in the future? "Whenever you get angry at your sister, you must tell her so."

(11) Is there an attempt to obtain more information regarding child feelings? "Can you tell me what you're upset about?"

(12) Is there an attempt to obtain more information regarding child behavior? "Tell me what happened."

This scoring system was designed to specify clearly how adults respond to children in problem situations with regard to three developmental issues. The first involved being aware of and concerned about the child's feelings (categories 1 and 10-12). This issue was presumed to relate to the development and maintenance of the child's feelings of self-esteem and worth. The second dealt with relating the child's feelings and/or behavior to adult's feelings and/or behavior (categories 2-6). These responses should bear some relationship to the child's development of interpersonal skill and competence (how one person affects another). The third involved the issue of communicating directions to the child regarding his behavior (categories 7-9 and 13). These responses should relate to the child's ability to master his environment through the socialization process (learning what he can do and how he can do it).

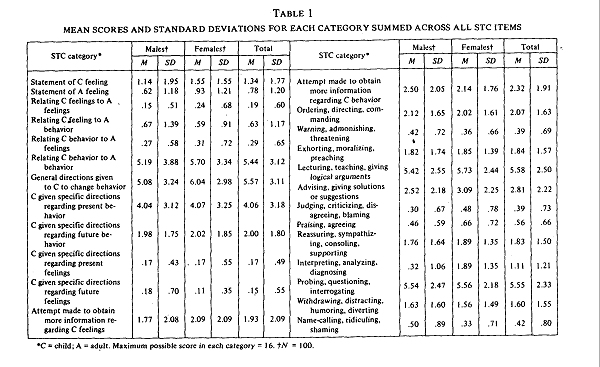

The responses were also coded for the 12 categories developed by Gordon (1970). (5) They can be found as categories 14-25 in Table 1.

Table 1

All categories were scored for each STC item as being present or absent in that item. Each item could be scored for more than one category, but a category could only be scored once for each item.

RESULTS

Reliability

Four undergraduate raters, unaware of the nature of the research project, were trained to score for the first 13 categories. After group training, the first reliability measures were computed by having them complete independently five additional protocols not included in the final analyses. Reliability was calculated by the percentage of agreement between each rater and an "expert" (E). Reliabilities ranged from 72% to 95% with an overall mean of 86%. To determine consistency of agreement, after completion of the scoring, three protocols were chosen at random from each of the raters and coded by E. These percentages of agreement ranged from 83% to 98% with an overall mean of 95%.

After completing the scoring of all STC's for the first 13 categories, the four coders were then trained to score for Gordon's 12 categories. The first measurement of percentage of agreement with the "expert" ranged from 80% to 98% with an overall mean of 92%. At the completion of the scoring E coded three additional protocols from those completed by each rater. These percentages of agreement ranged from 81% to 98% with an overall mean of 96%.

Analysis of Responses by Categories

The mean scores and standard deviations for each category summed across all STC items for males and females and the total group are shown in Table 1.

What stands out in Table 1 especially, with regard to the first 13 categories, is the relatively low mean scores. In the eight categories involving awareness and communication of either the feelings of the child or adult, or both, the mean scores never exceeded 2.0. In only three of the categories did the mean scores exceed 3.0 (categories 6-8); these categories involved only the behavioral aspects of the adult-child relationship rather than the affective components. It is clear that this group of adults only rarely focused their communication on their own or the child's feelings in situations that obviously involve strong feelings, needs, and wishes.

Analysis of Variance: Sex of Subject x Ownership of Problem

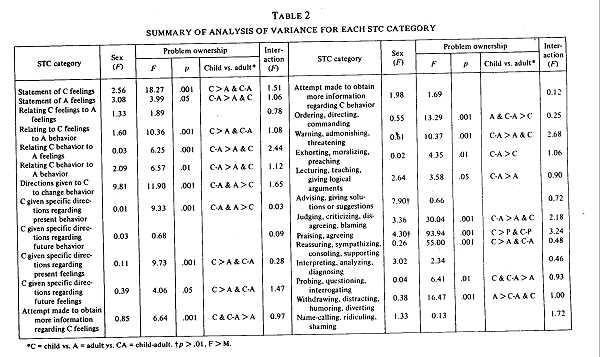

A 2 x 3 analysis of variance (Wirier, 1971) was performed for each STC category. The main effects of sex, problem-ownership, and the interaction of these factors were examined. When appropriate, the Newman-Keuls method (Winer, 1971) was used to study within variable differences. A summary of the results is shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Although no meaningful sex differences or interaction effects were found, the main effect of problem ownership did produce significant differences in the - adult responses. When the problem situation was primarily, and only, child owned (C > A and C-A), the adults responded with more statements of children's feelings, more statements relating child feelings to adult behavior, and more specific directions regarding the handling of present and future feelings. Adults also responded with more praising, agreeing, reassuring, sympathizing, consoling, and supporting responses than when the problems included adult needs being thwarted. When adult needs were involved (A and C-A > C) the adult made more responses giving directions to the child to change his present behavior and more ordering, directing, and commanding responses than when the problem was primarily and only child owned. In the specific case when the problem was equally owned by both the child and adult (C-A > A and/or C), the adult made more statements of his own feelings and more responses relating the child behavior to adult feelings and behavior, more warnings and threats, more moralizing and preaching responses, more lecturing and logical arguments, and more blaming, disagreeing, judging, and criticizing responses than when the problem was primarily owned only by the child or adult.

These results tend to support Gordon's (1970) contention that when adult's needs are involved in a problem situation the adult is likely to be more insensitive and destructive than when there is a confrontation centering around only the child's needs. In the latter case the adults focused their communication more on the child's feelings and how he or she could express them.

DISCUSSION

The discussion of the results must be preceded by the following qualifications:

(1) The behavior studied was limited to thought-out, written accounts of projected actions. As noted previously, the question of whether such behavior is predictive of actual social interaction is, at this time, unanswered. Current research (Stollak, 1973) is evaluating the immediate and long-term differences in the behavior of undergraduates, with varying STC scores, in their play interaction with children;

(2) The Ss were not a random or selected sample of parents but a limited sample of educated unmarried young adults with a specific positive set toward children, as indicated by their interest in participating (in fact competing for a position) in a project involving work with children; and

(3) Missing from the situations was a specification of adult mood and the affectional relationship between adult and child that existed at the time of the encounter that could significantly affect adult behavior (Becker, 1964).

One might expect that these limitations would result in more "homogeneous" responding by these Ss. But problem ownership did significantly affect adult behavior even in this projective situation. This finding has some relevance to the issue of direction of effect eloquently discussed by Bell (1971). The implications of reciprocal influences are seen most clearly in problem situations. If, an adult has ineffectively responded to a child's feelings and behavior, how then does this affect the child? On some level the child will react affectively to the adult's behavior (it will make the child feel one way or another). Herein is the first link in a reciprocal chain of frustrating communications. For example, on STC item 9, in which the child is found masturbating, most adults angrily tell the child to stop. If this occurs in real life, the child may then respond with some kind of self-defense, such as denying the act; the denial may in turn result in more anger from the adult or in passive acceptance and guilt. In either sequence the child perceives that his behavior has had some negative effect on the parent. Because the child does not want, to continually incur the wrath of his parents, he will take an inappropriate degree of responsibility in attempting to minimize parental anger. In the process he may deny his own feelings, and/or experience anxiety and guilt, which will in turn negatively affect future interactions in that his capacity for self-differentiation will be impaired.

To the extent that reciprocal adult-child influences are always operating, the notion of adult and child-owned problems might be qualified. In retrospect, this could be a somewhat misleading system of classification when we consider that any interaction between adult and child could be seen to involve the needs of both. However, the data from the present research point toward the existence of some dimension of need frustration and satisfaction affecting the ability of adults to respond sensitively to children in various problem situations.

Further, it may be that the interaction of child and adult needs in any given situation may be the more prepotent variable in determining what is communicated. If so, it follows that measuring the reciprocal effects of adult-child communication would reflect more accurately the interdependency of adult-child needs. Data from the present study may suggest a set to respond perhaps more indicative or predictive of attitudes than behavior. In this regard, studies aimed at dealing with microscopic sequential analyses of actual interaction (e.g., Moustakas and Schlalock,1955) would appear to be most useful.

A final point concerns the impetus for this research. The study of abnormal child psychology must adopt a perspective that extends beyond child behaviors that are so provocative that they impel an adult to bring the child to the attention of a mental health professional. It must also include the study of variables involved in the relative absence of positive personal and social behaviors in the child's repertoire. For example, Baumrind (1967) found that only 12% of a sample of bright young children (mean IQ of 123) of middle-class, well-educated parents met her criteria for competence. Why are loving, caring, generous, and altruistic acts not more frequent in children and adolescents? Why are the vast majority of children not highly imaginative and creative, not highly self-assertive, self-controlled, and self-reliant?

It is likely that the actions of adults toward children in problem situations not only contribute to the development of child behavior dysfunctions but also to the absence of self-actualization. The present findings suggest that future research will indicate that most adults, in real-life confrontations with children in problem situations, do not clearly convey understanding and acceptance of children's feelings, needs, and wishes; do not clearly communicate their own Feelings about the child's feelings and behavior; and do not provide the child with constructive solutions or outlets for their aroused needs. There is no question that, at present, we have little knowledge in these areas. As relevant information and evidence does accumulate, we will be able to develop and implement increasingly more effective therapeutic and education programs that will treat, prevent, and minimize child-behavior dysfunctions. Perhaps of even greater importance is the impact that such knowledge will have on the development and implementation of programs that are designed to maximize the total growth and humanness of every child.

1. The research reported in this paper was supported in part by Grant MH 16444 from the U.S. Public Health Service, National Institute of Mental Health.

2. Requests for reprints should be sent to Dr. Gary E. Stollak, Department of Psychology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48823.

3. The help of Lawrence Messe, Joel Aronoff, Luch Ferguson, and Albert Rabin is very gratefully acknowledged. We also wish to acknowledge the help of Kathy Barrie, Lew Borman, Deletha Crum, and Eli Karimi, who served as coders.

4. Copies of the STC are available from the senior author.

5. Detailed descriptions of each category, examples, and the possible effect of such adult responses can be found in Gordon (1970, pp. 41-44, 321-327). Although many of these category titles do not seem to imply "destructive" adult behavior and appear to overlap with the first 13 categories, a close reading of Gordon's definitions and examples of each category will indicate their minimal overlap and their undesirability. For example, rather than being similar to categories 1-5, Gordon includes under Reassuring, Sympathizing, Consoling, and Supporting (category 21) behaviors such as "talking him out of his feelings, trying to make his feelings go away, denying the strength of his feelings [p. 43] ."

REFERENCES

Axline, V. Play therapy. New York: Ballantine Books, 1969.

Baumrind, D. Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genetic Psychology Monographs, 1967, 75, 43-88.

Baumrind, D. Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monograph, 1971, 4, (No. 1, Part 2).

Becker, W. C. Consequences of different kinds of parental discipline. In M. L. Hoffman and L. W. Hoffman (Eds.), Review of child development research, New York: Russell Sage, 1964.

Bell, R. Q. Stimulus control of parent or caretaker behavior by offspring. Developmental Psychology, 1971, 4, 63-72.

Buckley, N. K., and Walker, H. M. Modifying classroom behavior: A manual of procedure 'for classroom teachers. Champaign, Ill.: Research Press Co., 1970.

Coopersmith, S. The antecedents of self-esteem, San Francisco: W. H. Freeman, 1967.

Dreikurs, R. Psychology in the classroom. New York: Harper and Row, 1968. 3inott, H. Between parent and child. New York: Macmillan, 1966.

3ordon, T. Parent effectiveness training. New York: Wyden, 1970.

3aley, J. Strategies of psychotherapy. New York: Grune and Stratton, 1963. 3atfield, J. S., Ferguson, L. R., and Alpert, R. Mother-child interaction and the socialization process. Child Development, 1967, 38, 364-412.

Hawkins, R. P., Peterson, R. F., Schweid, E., and Bijou, S. W. Behavior therapy in the home: Amelioration of problem parent-child relations with the parent in a therapeutic role. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 1966, 4, 99-107.

Jackson, P. H. Verbal solutions to parent-child problems. Child Development, 1956, 27, 339-349.

Leighton, L., Stollak, G. E., and Ferguson, L. R. Patterns of communication in normal and clinic families. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 1971, 36, 252-256.

Moustakas, C. E. The authentic teacher. Cambridge, Mass.: H. A. Doyle, 1966.

Moustakas, C. E., and Schlalock, H. D. An analysis of therapist-child interaction in play therapy. Child Development, 1955, 26, 143-157.

Patterson, G. R. Behavioral intervention procedures in the classroom and in the home. In A. E. Bergin and S. L. Garfield (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. New York: Wiley, 1971.

Saxe, R., and Stollak, G. E. Curiousity and the parent-child relationship. Child Development, 1971, 42, 373-384.

Stollak, G. E. An integrated graduate-undergraduate program in the assessment, treatment, and prevention of child psychopathology. Professional Psychology, 1973, 4, 158-169.

Sulzer, B., and Mayer, G. R. Behavior modification procedures for school personnel. Hinsdale, Ill.: Dryden, 1972.

Wimberger, H. C., and Kogan, K. L. Interpersonal behavior ratings. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 1968, 147, 260-271.

Winer, B. J. Statistical principles in experimental design. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1971.

neurodiversity.net

Reproduced without permission of the author, for educational purposes only, according to the Fair Use doctrine.